Why do agile process models work or fail?

When math teaches about life

Today you literally cannot escape agile processes. Scrum. Kanban boards. Kaizen. Isn’t all of our business Toyota? And the promises sound great. Each step an improvement. How could that be bad? Understand the goal, understand the efforts required, break it down into manageable steps. Then sprint. Review and improve, in each dimension. Everybody is doing it.

It did help Toyota in the documented areas, but not to the extent of being the #1 company worldwide, yet the promise is just following it will make any other company #1. Many frustrated people are an indication something is not right, but the universal answer is: It’s them. They are doing it wrong. They need more education. They need to give up their silent resistance against change. Amidst all arguments, I wonder why nobody talks about the math elephant in the room. (For some reason, a question people outside engineering don’t ask as often.)

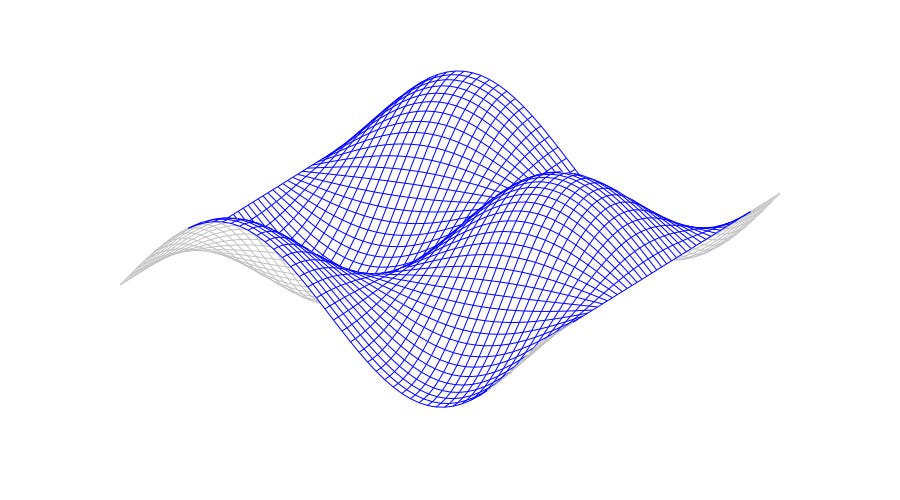

Steady improvement is optimization. What’s the first question in optimization? The nature of the objective function.

Convex objective functions are great, because even without a global view, you can continuously improve without ever getting lost. You know when you are done, in absolute terms. If you do it wrong, you may do many baby steps and improve little with much effort, but at least you don’t move backwards. The constraints may be tough to model. Nobody said it’s easy, but it is possible. Many objective functions are convex, or can be made convex, if ‘good enough’ suffices.

Not convex objective functions are the opposite. They exhibit local maximums with dips in between. You may need to step back in order to improve. Without a global view, you don’t know if that will be worth it. You may get lost. That’s when you need, as Steve Jobs called them, „… the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward.“ Pretty disruptive. Not quite the typical micro-managed agile world of continuous risk-estimated improvement.

Alternatively, you can simply ignore the nature of the objective function and proceed with convex optimization. You may get lucky to reach the global maximum, but more likely get stuck in a local one. If you cannot refine it and break down the work, it is not ready to be done. Keep trying until you can make a baby step. That’s when people start to argue. When they doubt the process model. Yet, managers have seen it working before, so clearly the workers are at fault. Right?

Not surprisingly, apart from being applied to wrong areas, Kaizen and associated processes have a bad history of being abused to press workers into compliance and uniformity while relieving managers from being responsible for the working conditions, because everybody just follows ‘the proven system’ that cannot be questioned.

Research & Development: One term, but two areas that could not be more different. One characterized by exploration of the unknown, the other navigating efficiently in charted territory, except sometimes one quickly turns into the other. One pretty certain not convex, unlike the other.

The title image shows a two-dimensional function that is not convex, with dips and local maximums. In between peak and valley it appears clear how to improve, but the way may be leading towards the wrong peak. Yes, the peaks have different heights.